Budget Surplus vs Deficit: What Really Impacts Your Wallet

Budget surplus means a government’s revenues exceed its spending during a fiscal period, allowing it to pay down debt or save for future needs.

Budget deficit happens when a government’s spending surpasses its revenues, forcing it to borrow money and add to the national debt.

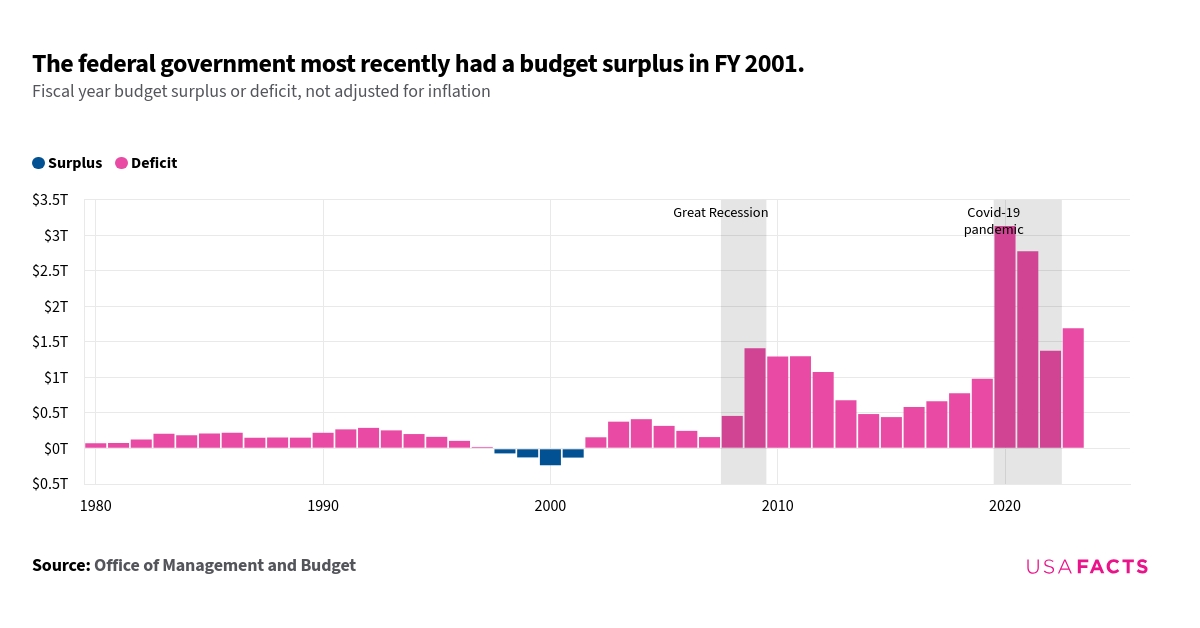

The last time the U.S. government had a budget surplus was in 2001, showing an extra $236 billion in its accounts. Federal spending has outpaced revenue steadily for more than two decades. The budget deficit has now hit a massive $2.0 trillion in 2024.

These budget numbers affect your daily life more than you might think. Every American’s wallet feels the effects through changes in tax rates and public services. Understanding these economic concepts is vital because they shape our financial future.

The stakes are even higher now. The government pays $892 billion annually just in interest on the national debt. This big expense influences policy decisions that directly affect the average citizen’s cost of living.

- Budget surplus means government revenues exceed spending, while budget deficit means spending exceeds revenues.

- Deficits grow during recessions, wars, or crises (e.g., COVID-19), while booms can create surpluses (e.g., Clinton era 2000).

- The U.S. deficit hit $2.0 trillion in 2024, with interest payments now costing $892 billion annually.

- Surpluses can lead to tax cuts, service expansion, and debt reduction; deficits often bring higher taxes and service cuts.

- Deficits increase national debt and borrowing costs, which can slow economic growth and lower credit ratings.

- Private savings rise modestly in response to deficits, but not enough to fully offset lost government savings.

- Long-term risks include higher interest rates, reduced investment, and weaker future economic growth.

Budget Surplus vs Deficit: Definitions Made Simple

Understanding how governments manage money starts with learning the key difference between budget deficits and budget surpluses. These concepts shape economic policies that affect everyday citizens.

Budget deficit definition and how it works

A budget deficit happens when government spending exceeds its revenue in a fiscal year. The government must borrow money to cover this gap by selling Treasury bonds, bills, and other securities to investors. This borrowed money adds to the national debt, which includes all past deficits plus interest.

The federal budget deficit hit $1.70 trillion in fiscal year 2023, which was 6.1% of the nation’s GDP. This number helps put the deficit in perspective compared to the whole economy.

Several factors affect the size of a deficit:

- Economic conditions: Tax revenues drop during downturns as people earn and spend less, while spending on programs like unemployment insurance goes up

- Policy decisions: Tax cuts, stimulus packages, and new spending programs can make deficits bigger

- Unexpected events: The COVID-19 pandemic caused the deficit to jump from $983.60 billion in 2019 to $3.10 trillion in 2020

Budget deficits aren’t always bad. All the same, high deficits that last too long, especially during good economic times, might lead to higher interest payments and less investment.

Budget surplus definition economics explained

What is a budget surplus? Money comes in when government revenues are more than what it spends during a fiscal period. This lets governments reduce existing debt or save for future needs.

Budget surpluses don’t happen often in the United States. The federal government has achieved a surplus just 12 times since 1933, with the last one in 2001.

Economists like budget surpluses because they show the government manages its money well. It also gives flexibility to handle economic challenges without taking on more debt. A surplus occurs when:

- Tax revenues grow during economic booms

- Government keeps spending under control

- Leaders make fiscally responsible choices

- Money coming in beats money going out

But surpluses aren’t always good in every situation. Trying to keep a surplus during recessions through higher taxes or spending cuts could make economic problems worse.

Balanced budget: when spending equals revenue

A balanced budget strikes the middle ground—government revenues match its spending exactly. Simple as it sounds, true balanced budgets rarely happen because economic factors keep changing.

Balanced budgets work in different ways:

- Annual balance: Money in equals money out within one fiscal year

- Biennial balance: Extra money one year makes up for shortfalls in another

- Cyclical balance: Deficits during bad times balance out with surpluses during good times

People who support balanced budgets say they help governments:

- Control spending and focus on what matters most

- Stop debt from burdening future generations

- Keep control over financial decisions and policies

Critics say strict balanced budget rules limit the government’s power to fight economic crises. Many economists believe temporary deficits act as “automatic stabilizers” during tough times by supporting consumer spending.

Learning about budget surpluses and deficits helps citizens see how government money decisions end up affecting their wallets through taxes, services, and economic conditions.

What Causes a Surplus or Deficit in Government Budgets

Government budgets swing between surplus and deficit based on many factors. These driving forces explain why the federal balance sheet changes as time goes by.

Economic cycles: booms vs recessions

The state of the economy largely determines government budget balances. Budget deficits usually shrink (or surpluses grow) during strong economic periods. Two main reasons explain this pattern:

Tax revenues naturally go up as businesses make more profits and people earn higher incomes. The government also spends less on social safety nets because fewer people ask for help.

The opposite happens during economic downturns:

- Tax revenues drop as incomes fall

- More money goes to programs like unemployment insurance

- The government gets less money but pays out more

Most economists see these cyclical deficits as helpful “automatic stabilizers” that soften the blow of recessions. They prevent economic downward spirals by supporting consumer spending when private spending drops.

Policy decisions: tax cuts, stimulus, and spending

Beyond economic ups and downs, policy choices shape budget balances. Here’s what matters:

Tax policies: Tax cuts can reduce government revenue by huge amounts. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act shows this clearly – it cut federal revenue by $1.65 trillion from 2018 to 2027.

Spending decisions: More money for Social Security, Medicare, or military programs means higher spending. Money put into infrastructure, education, and healthcare costs a lot now but might pay off later.

Fiscal philosophy: Balanced budgets were the gold standard before the early 20th century. Keynesian economics changed this view, making deficit spending an accepted tool to stabilize the economy.

Governments might face “structural deficits” even in good economic times. These ongoing gaps often come from basic mismatches between how much money comes in and how much goes out.

Unexpected events: wars, pandemics, and bailouts

Sudden events can throw budget forecasts off course. Recent examples tell the story:

COVID-19 pandemic: The federal response reached about $5.60 trillion in relief measures. This pushed the deficit to 14.9% of GDP in 2020—the biggest since World War II.

Military conflicts: Long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan pushed government spending way up without bringing in extra money.

Financial crises: The government’s answer to the 2008 Great Recession included big bailout packages that pushed the deficit to 9.8% of GDP in 2009.

Natural disasters: Bad weather often means quick federal spending on relief and recovery.

These emergency responses usually mean bigger deficits in the short term. Most economists think such temporary measures make sense, even if they raise long-term budget concerns.

These factors help explain why government budgets change and how these shifts affect everyone’s financial health.

How Budget Surplus vs Deficit Affects Your Wallet

Federal budget decisions shape your personal finances in ways you might not realize. These choices determine how much money stays in your pocket, what services you receive, and your overall purchasing power.

Tax changes: more or less money in your paycheck

Budget surpluses create room for tax relief. The government might return extra funds to citizens through tax cuts or credits if it collects more than it spends. State surpluses can reduce taxes or support targeted tax relief programs.

Growing deficits could lead to higher taxes. The government’s mounting debt brings rising interest payments—reaching $892 billion in 2024. This squeeze on the budget might force changes in tax policy that reduce your take-home pay.

Public services: what gets funded or cut

Your daily life depends on public services that budget balances affect directly. Governments face tough choices about program funding during deficit periods:

- Medicare funding might shrink

- Infrastructure projects get pushed back

- Education and research face budget cuts

Budget surpluses offer chances to expand or create new services. Australia announced an additional $8.5 billion investment in Medicare that will ensure nine out of ten GP visits become bulk billed by 2030.

Inflation and interest rates: cost of living impact

Budget deficits can drive up inflation and interest rates, affecting your cost of living. Large deficits, especially those funded through monetary expansion, increase inflation risks. Your purchasing power drops as everyday items become pricier.

Higher deficits usually mean higher interest rates as government borrowing increases. This raises costs for:

- Mortgages and home loans

- Auto financing

- Credit card debt

- Student loans

These changes ripple through the economy. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell explains, “When the government runs structural deficits and borrows large amounts even in good economic times, that borrowing is more likely to have harmful effects on private credit markets and hurt economic growth”.

Budget decisions create long-lasting effects. Your financial well-being could feel these impacts years later, from retirement savings to housing costs.

Surplus vs Deficit: Long-Term Effects on the Economy

Government budget balances alter the economic map for decades ahead. The effects take time to materialize but they deeply shape our nation’s prosperity.

Debt accumulation and interest payments

Budget deficits steadily increase the national debt and create a financial burden that grows over time. The federal debt reached 100% of GDP in 2024 and experts project it to climb to 118% by 2035. This growing debt creates a troubling cycle where rising debt leads to higher interest payments.

Interest costs have skyrocketed recently, hitting $892 billion in 2024—about 13% of total federal expenditures. These payments will exceed Social Security spending by 2044. The escalating interest costs leave fewer resources to fund education, infrastructure, and healthcare.

Effect on GDP and national credit rating

Budget balances and economic growth share a significant relationship. Research shows that declining budget surpluses or rising deficits reduce national saving and future income. Long-term interest rates typically rise by 50-100 basis points for each percentage increase in projected budget deficits.

America’s fiscal deterioration has already caught rating agencies’ attention:

- Fitch downgraded the U.S. credit rating from AAA to AA+ in 2023

- Moody’s lowered its outlook to “negative” citing large deficits

- All but one of these major rating agencies expressed concerns about America’s fiscal path

These downgrades raise borrowing costs and might trigger a negative cycle that disrupts financial markets and the ground economy.

Private sector savings and investment trends

Government budget positions shape private sector behavior uniquely. Private saving tends to increase somewhat as deficits rise—though not enough to completely offset government borrowing.

Economists call this “Ricardian equivalence,” which suggests that households prepare for future tax increases to cover current deficits. Research shows that private saving increases by about 30 cents for every dollar of government borrowing.

Budget surpluses create room for private investment. Persistent deficits can reduce capital formation, productivity, and living standards across generations. This shows why the surplus vs deficit debate extends beyond today’s budget discussions.

Real-World Examples: U.S. Budget Trends Over Time

Image Source: USAFacts

American budget history gives us ground insights into the surplus vs deficit debate. Specific time periods show how economic policies affect government finances and ended up impacting citizens.

The Clinton-era surplus: what happened in 2000

The year 2000 marked a remarkable fiscal achievement—a budget surplus of $237 billion. This was the third consecutive surplus and largest in American history. Several key factors contributed to this financial milestone:

President Clinton started by implementing tax increases on upper-income taxpayers early in his presidency. His administration managed to keep spending under control, especially in defense. The dot-com boom generated unprecedented tax revenue from capital gains and rising salaries.

These surpluses helped the government reduce publicly held debt by $363 billion between 1998-2000. A family with a $100,000 mortgage saved roughly $2,000 annually in payments because of this debt reduction.

COVID-19 deficit spike: 2020–2021 explained

The pandemic dramatically changed America’s fiscal path. The federal deficit more than tripled from $983.60 billion in 2019 to an astounding $3.10 trillion in 2020. This amount represented 14.9% of GDP—the largest ratio since World War II.

The government launched five major fiscal relief measures that totaled $5.60 trillion. These included:

- Expanded unemployment insurance

- Direct stimulus checks to Americans

- Financial support for small businesses

- Healthcare system funding

Revenue increased from approximately $3.50 trillion in 2019 to $4.00 trillion in 2021. The massive emergency spending still pushed the deficit to historic levels. The deficit reached $2.775 trillion in 2021, becoming the second-largest in history.

Current 2025 outlook: where we stand now

The fiscal picture remains challenging today. The projected deficit for 2025 stands at $1.90 trillion (6.2% of GDP), making it the third-highest figure in American history.

Federal debt has hit 100% of GDP in 2025. Projections show it climbing to 118% by 2035, which surpasses the previous high of 106% after World War II. Interest payments now take about 18% of federal revenue, up from just 9% in 2021.

Growth forecasts remain modest. Experts project 2.1% growth in 2025 and an average of only 1.8% annually over the next decade. These numbers point to ongoing fiscal challenges ahead.

Comparison Table

| Aspect | Budget Surplus | Budget Deficit |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Government revenues exceed expenditures during a fiscal period | Government spends more money than it collects in revenues during a specific period |

| Last US Occurrence | 2001 ($236 billion surplus) | Currently ongoing (2024: $2.0 trillion deficit) |

| Effect on Economic Growth | Creates flexibility for economic challenges and shows strong financial management | Reduces investment opportunities and leads to higher interest payments |

| Effect on Public Services | Enables service expansion and new investments | Results in program cuts and delayed infrastructure projects |

| Effect on Taxes | Enables tax relief or credits | Often requires tax increases to close the gap |

| Interest Payments (2024) | Helps reduce debt payments | $892 billion annually in interest payments |

| Key Causes | – Strong economic expansion – Controlled government spending – Fiscal restraint – Revenue exceeding expenditures | – Economic downturns – Policy decisions (tax cuts, stimulus) – Unexpected events (wars, pandemics) – Increased program spending |

| Effect on National Debt | Enables debt reduction | Adds to national debt burden |

| Recent Example | Clinton era (2000): $237 billion surplus | COVID-19 response (2020): $3.10 trillion deficit |

Conclusion

Everyone needs to know how budget surpluses and deficits work to secure their financial future. The massive $2.0 trillion deficit and $892 billion yearly interest payments affect Americans through possible tax changes, public services, and the cost of borrowing money.

The history of government spending tells an interesting story. We’ve seen everything from surplus budgets during Clinton’s presidency to huge deficits during COVID-19. These decisions by the government have shaped our economy in significant ways. The economic picture for 2025 doesn’t look much better. Deficits will likely stay high, and federal debt will be bigger than what our entire country produces in a year.

These budget realities touch our daily lives in many ways. When interest rates go up, people pay more for mortgages and loans. The government’s growing debt payments mean less money for important public services. While deficits can help during tough times, constant budget gaps could hurt our economy’s long-term health.

Americans should keep track of these budget changes because they affect their retirement savings and housing costs. The financial decisions our government makes today will without doubt create ripple effects for future generations.