Money Supply Explained: Why M1 and M2 Matter for Your Financial Future

The U.S. money supply reached a staggering $18.46 trillion by January 2025, posing a significant impact on the economy. Money supply measures the total amount of cash and cash equivalents that move through an economy at any given time.

M1 has coins, currency, and checkable deposits, while M2 adds short-term time deposits and money market funds to these components. The Federal Reserve monitors these measurements carefully to prevent inflation and deflation, though its approach has changed through the years.

These concepts help explain how changes in the money supply affect prices and employment levels in today’s economy.

- Money supply measures total liquid assets (cash, deposits) circulating in an economy, influencing inflation and growth.

- M1 includes cash and checkable deposits; M2 adds savings accounts, CDs under $100K, and money market funds.

- Liquidity distinguishes money types—M1 is highly liquid for transactions, M2 is less liquid for savings/investments.

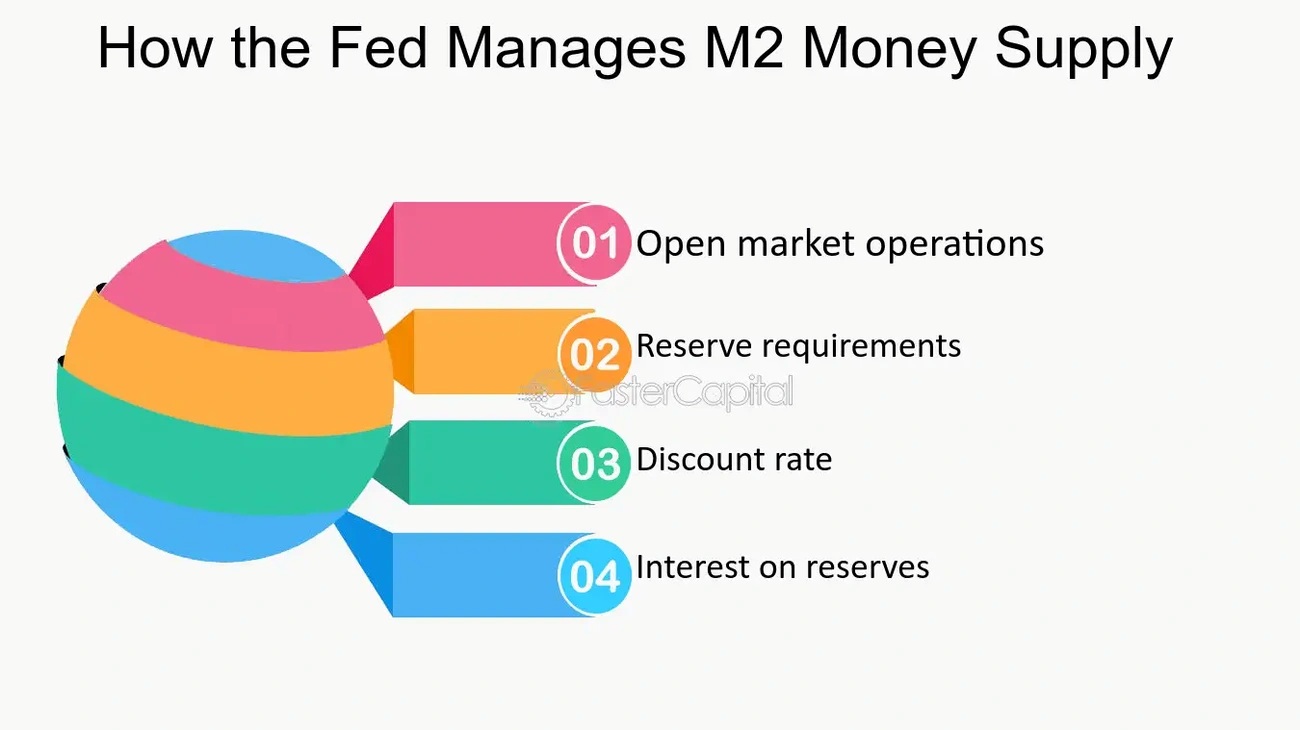

- The Fed controls money supply via open market operations, interest on reserves, and (historically) reserve requirements.

- Money supply expansion tends to lower interest rates and boost inflation; contraction does the opposite.

- Fed policy shifted from targeting money supply to focusing on interest rates after weakening money-GDP links post-1980s.

- Investors track M1/M2 trends to adjust portfolios toward stocks, real estate, or fixed income depending on liquidity conditions.

Understanding the Basics: What Is Money Supply?

Modern economies rest on money supply as their foundation. It represents the total volume of currency and liquid assets that move through the system at any given time. This measure shapes how financial systems work and affects everything from interest rates to inflation.

Money supply definition and why it matters

Money supply includes all liquid assets that households and businesses can use to make payments or keep as short-term investments. The system takes in cash, coins, and bank account balances that flow through an economy.

Money supply does more than just measure economic activity. The Federal Reserve and other central banks watch it closely because it relates to vital economic variables like nominal gross domestic product and price levels. These figures help central banks set monetary policy, though they look at many other financial indicators too.

Changes in the money supply can substantially affect economic activity. When the money supply grows faster than economic output, the economy typically experiences inflation. The opposite happens when the money supply shrinks—economic activity often slows down and leads to disinflation or deflation.

Types of money: M0, M1, M2, and beyond

Experts group money supply into different “monetary aggregates” based on how liquid they are:

- M0/Monetary Base: The total of currency in circulation and reserve balances that banks keep at the Federal Reserve

- M1: Public currency plus transaction deposits at depository institutions

- M2: M1 plus small-denomination time deposits (less than $100,000) and retail money market mutual fund shares

- M3: M2 plus large and long-term deposits

- MZM (Money Zero Maturity): Financial assets you can redeem at par on demand

The Federal Reserve tracks and reports M1 and M2 figures regularly to understand economic conditions. These measurements have evolved from commodity-based money to today’s fiat currency system.

How liquidity defines different money categories

Liquidity shows how fast and easily an asset can be turned into cash without losing value. This idea helps classify different types of money.

Monetary aggregates follow a clear pattern of liquidity. M0 and M1 components work mainly as exchange mediums—they let transactions happen right away. M2’s additional components serve mainly as value stores.

Cash is the most liquid asset, followed by checking accounts and savings deposits. However, as we move from M1 to broader measures like M2 and M3, assets become harder to convert to cash.

Central banks use different measures based on what they want to achieve. M1 shows money ready for immediate transactions, while M2 tells us about possible future spending.

Breaking Down M1 and M2 Money Supply

Money flows through the economy in different components that we can break down to understand better. The Federal Reserve tracks these monetary assets by using specific categories. M1 and M2 measurements are their main focus.

M1 money supply: cash, demand deposits, and checkable accounts

M1 represents money components you can access right away for transactions and purchases. M1 had three main elements before May 2020: currency outside financial institutions, demand deposits at commercial banks, and other checkable deposits.

Currency in circulation refers to all physical coins and bills that people and businesses hold, except those in bank vaults or at the Federal Reserve. This makes up the money supply’s most tangible part.

Demand deposits are the balances in commercial banks’ checking accounts. You can use these funds right away through checks or debit cards.

Other checkable deposits started with NOW accounts (Negotiable Order of Withdrawal) and ATS accounts (Automatic Transfer Service) that work just like checking accounts.

The Federal Reserve made a big change in May 2020 when it added savings deposits to M1, which expanded this measure by a lot.

M2 money supply: savings accounts, time deposits, and money market funds

Image Source: FasterCapital

M2 has everything in M1 plus other assets that aren’t quite as easy to access. Small-denomination time deposits (under $100,000) and retail money market funds are part of M2.

Small-denomination time deposits, which most people know as certificates of deposit (CDs), earn higher interest rates when you keep your money in for a set time. You’ll pay penalties if you take the money out early.

Money market funds take deposits from individual investors and buy short-term, low-risk securities like Treasury bills. These accounts give you better returns than regular savings accounts and you can still get your money fairly quickly.

M1 vs M2 money supply: key differences and overlaps

M1 and M2’s main difference comes down to how easily you can access your money and what it’s used for:

- Liquidity differences: You can use M1 components right away, but M2 assets take extra steps to turn into cash.

- Usage patterns: M1 money goes to things you need to buy now, while M2 components work better as short-term savings or investments.

- Interest characteristics: M1 elements don’t earn much interest, but M2 components like CDs and money market funds pay more because they’re harder to access.

- Economic significance: M1 shows what people can spend now, while M2 points to what they might spend later.

These measures help us learn about the economy. The relationship between M1 and M2 can show how people’s saving habits or confidence in the economy are changing. Economists watch these combined numbers to predict inflation trends and economic activity.

How the Federal Reserve Influences the Money Supply

The Federal Reserve plays a vital role in managing money circulation through several powerful tools. The Fed’s actions as the United States central bank directly affect both M1 and M2 money supply measures. These measures end up affecting everything from interest rates to economic growth.

Open market operations and reserve requirements

Open market operations (OMOs) serve as the Fed’s main tool for implementing monetary policy. The Fed buys and sells Treasury securities in the open market to control the money supply. When the Fed buys securities, money flows into the banking system. The opposite happens when it sells securities—money leaves circulation.

The process works in a straightforward way:

- Buying securities: The Fed adds money to banks’ reserve accounts, which increases reserves and lets them lend more

- Selling securities: The Fed cuts bank reserves, which reduces their lending ability

Reserve requirements used to be another important policy tool. Banks had to keep a percentage of deposits as reserves, either as vault cash or deposits with Federal Reserve Banks. The Fed could influence banks’ lending capacity and the money supply by adjusting these requirements.

The Fed set the reserve ratio to zero in March 2020. This decision showed that reserve requirements no longer played a major role in modern monetary policy.

Interest on reserves and its effect on M1 and M2

In October 2008, the Fed started paying banks interest on reserve balances (IORB). This new tool changed the way monetary policy works.

Interest on reserves sets a “floor” for short-term interest rates. Banks won’t lend at rates lower than what they earn on their reserves. The Fed can influence broader market interest rates by adjusting this rate without changing the money quantity.

This system has significantly changed M1 and M2 growth patterns. When banks earn interest on their reserves, they are more likely to hold extra reserves instead of giving out loans. This can slow down the growth of broader money measures even when the monetary base increases.

Why the Fed no longer targets money supply directly

The Fed focused on controlling money supply growth during the 1970s and early 1980s. This approach lost favor for several good reasons.

The connection between money supply and economic measures like GDP growth and inflation became less reliable. New financial tools and changing bank practices weakened the predictable connection between reserves and broader money measures.

The Fed officially announced it would stop setting target ranges for money supply growth when the Humphrey-Hawkins legislation expired in 2000. Now the Fed focuses on interest rates as its main policy tool, especially the federal funds rate—what banks charge each other for overnight loans.

This change proved essential during economic crises. The Fed used large-scale asset purchases (quantitative easing) to stabilize markets and boost the economy during both the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. This shows how the Fed has grown beyond just targeting money supply.

Why M1 and M2 Matter for Your Financial Decisions

Your financial decision-making improves when you understand how M1 and M2 money supply changes work in practice. These monetary measurements shape your purchasing power, investment returns, and overall financial well-being.

How changes in M1 and M2 affect inflation and interest rates

A basic economic principle connects money supply and inflation: inflation follows when money supply grows faster than economic output. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated this principle. M2 growth reached 26.9% year-over-year in February 2021, which led to inflation hitting 9.1% by June 2022.

Money supply and interest rates share an inverse relationship. A growing money supply drives interest rates down and makes borrowing cheaper. The opposite happens when money supply shrinks – interest rates climb and borrowing gets pricier. This relationship affects everything from mortgage rates to credit card interest.

M2 expanded to roughly 73% of the U.S. economy’s size by April 2022. This marked a substantial increase from 55% in 2009.

Real-life example: money supply changes during economic crises

The Federal Reserve expanded the monetary base by over 120% during the 2008 financial crisis. Banks held the money as reserves instead of lending it out, which prevented the feared inflation from materializing.

The COVID-19 pandemic created another extraordinary monetary expansion. M1 money supply grew fourfold to nearly $16.6 trillion by June 2020 and peaked at $20.6 trillion in 2022. This rapid growth helped drop unemployment from 14.8% to 6.1% within a year, though it later sparked inflation.

Using money supply trends to make smarter investment choices

Money supply trends can guide your investment decisions:

- During monetary expansion periods, look at:

- Growth-oriented investments like stocks and real estate that thrive with increased liquidity

- Hard assets that tend to hold value during inflationary times

- During monetary contraction phases:

- Fixed-income assets become more appealing as interest rates rise

- Defensive investments that excel in tighter monetary conditions

A needs-based strategy with diverse investments helps you navigate monetary policy changes for long-term financial planning. Financial experts recommend separating short-term and long-term investments to avoid emotional reactions to market swings caused by money supply changes.

Conclusion

Money supply measurements are vital economic indicators that guide financial decisions nationwide and personally. M1 and M2 metrics help people understand how monetary policies affect their everyday lives and financial future.

History shows how changes in money supply affect economies. The massive expansion during COVID-19 and the 2008 financial crisis proved that monetary policy can stabilize economies. These same policies created new challenges like inflation. These examples show why tracking money supply helps people make better financial decisions.

Savvy investors know that money supply trends are a great way to get portfolio management insights. These metrics help them adjust investment strategies as economic conditions change. Knowledge of M1 and M2 movements gives investors an advantage when choosing between stocks and bonds or buying real estate.

The connection between money supply and inflation and interest rates keeps changing. Financial markets grow more complex each day. Staying updated about these basic economic measures helps achieve financial success in the long run.