Reserve Requirements: The Bank Rule That Shapes Your Money

The Federal Reserve made a groundbreaking move in March 2020 by setting bank reserve requirements to zero percent – something unseen since 1863. The original requirements made banks keep up to 25% of their deposits as reserves. We have seen many changes over the last several years, and these banking rules changed by a lot with rates between 7% to 13% for different types of banks.

Bank reserve requirements shape how banks handle money and determine their knowing how to lend to businesses and people. This vital tool builds public trust in the banking system and lets the Federal Reserve control financial system’s liquidity.

- Reserve requirements mandate how much liquid cash banks must hold instead of lending out—historically up to 25% of deposits.

- The Fed cut reserve ratios to 0% in March 2020, freeing up liquidity to support lending during COVID-19 and ending their use in monetary policy.

- Banks used to follow a tiered system with 0%, 3%, and 10% ratios based on deposit sizes under Regulation D.

- Required reserves can be met with vault cash or Fed account balances, and are calculated on lagged averages from transaction accounts.

- Zero-reserve policy enabled more lending, lowering borrowing costs but raising financial risk concerns.

- The Fed still adjusts exemption thresholds annually, even though reserve ratios remain at zero.

- Reserve requirements affect loan availability, interest rates, and monetary control, and may return as a policy tool if conditions shift.

What Is a Reserve Requirement and Why It Exists

Reserve requirements are the lifeblood of modern banking regulations. Banks don’t work like regular businesses; they follow special rules about managing their customers’ money.

Reserve requirement definition in simple terms

Reserve requirements are rules set by central banks that tell commercial banks how many minimum amount of liquid assets they must keep. These rules specify what percentage of customer deposits banks must keep ready instead of lending or investing.

Let’s say a bank has a 10% reserve requirement. If someone deposits $100,000, the bank must keep $10,000 either as cash in its vault or in its central bank account. The bank can then lend or invest the remaining $90,000.

Banks can keep their reserves in two ways:

Vault cash – Physical currency stored at the bank

Central bank deposits – Electronic balances maintained at the Federal Reserve or other central banks

The cash reserve ratio or reserve ratio refers to the percentage of deposits banks must hold. This ratio changes between banking systems and shifts based on economic needs and policy goals.

The Federal Reserve used a tiered system before March 2020. Small deposits had no requirements, medium-sized deposits needed 3% reserves, and larger deposits required 10%.

Why central banks enforce required reserves

Central banks have solid reasons to require reserves that go beyond basic regulation.

These requirements build public trust in banking. Since banks only keep part of deposits on hand—called fractional-reserve banking—reserves reassure people that banks can handle regular withdrawals.

Reserve requirements also protect banks from sudden mass withdrawals and prevent bank runs. Banks that run short on reserves can borrow from other banks or, in emergencies, from the central bank as the “lender of last resort”.

These requirements do more than protect individual banks – they help control monetary policy. Central banks adjust requirements to manage money supply and interest rates. They might lower requirements so banks can lend more money and boost the economy during tough times.

The Federal Reserve reduced reserve requirements to zero percent in March 2020 during COVID-19. This meant banks could lend freely from their deposits.

Reserve requirements serve both microprudential and macroprudential roles in finance. They protect individual banks while making the whole financial system stronger against broad risks.

Central banks use reserve requirements to:

Control fast credit growth risks

Reduce payment system problems

Protect customer deposits

These multiple uses make reserve requirements valuable tools as central banks balance growth with financial stability.

How Reserve Requirements Work in Practice

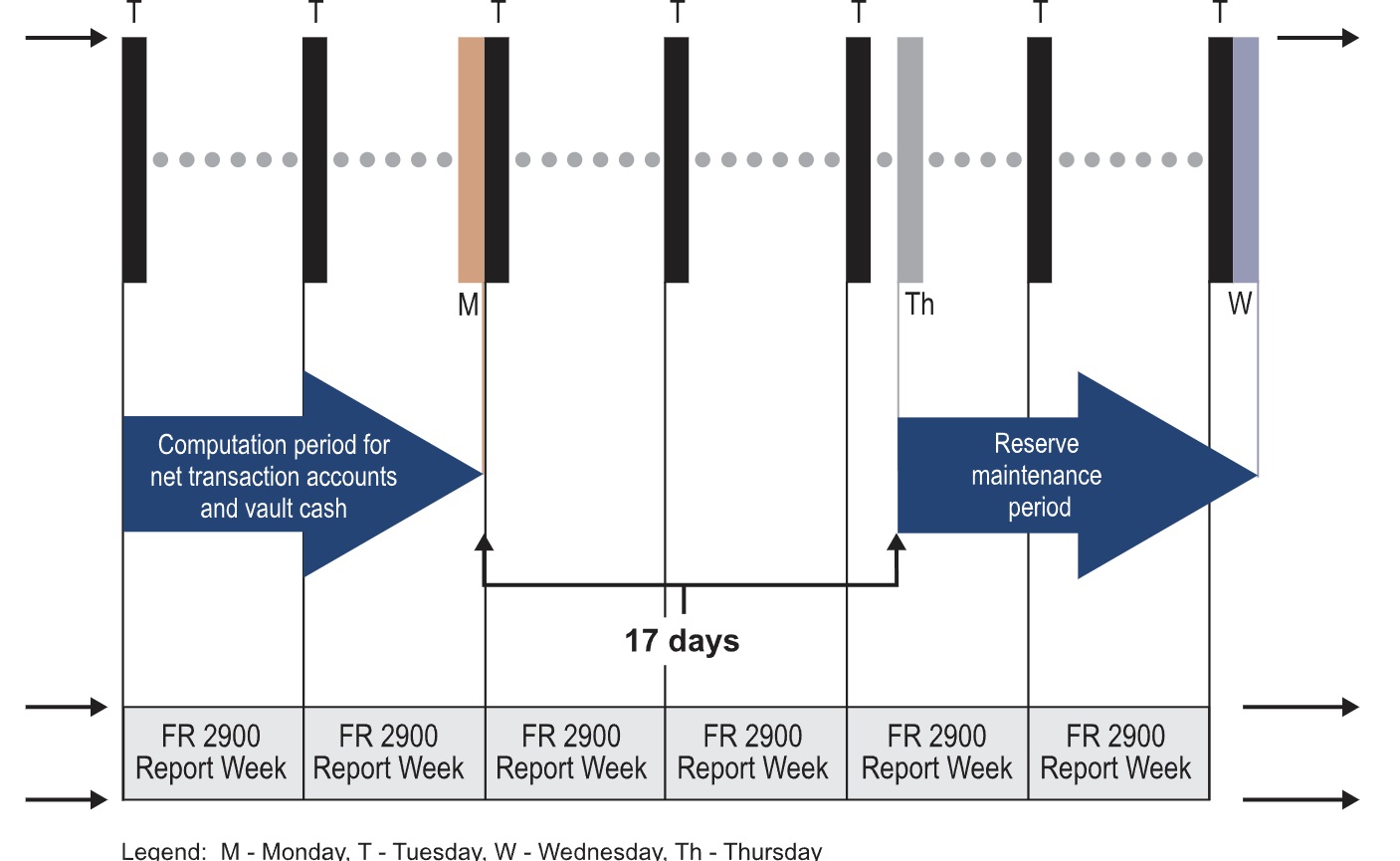

Image Source: Federal Reserve Board

Banks and central banks need exact calculations and regular monitoring to put reserve requirements into practice. The Federal Reserve has set the reserve ratio to zero for now, but knowing how these mechanics work helps us learn how banking systems operate.

How banks calculate required reserves

Banks figure out their required reserves by applying the reserve ratio to their “reservable liabilities” – these are mainly transaction accounts like checking accounts. The bank takes the average of these deposits during a set time period. Then it multiplies this average by the reserve ratio percentage.

To name just one example, a bank with $500 million in deposits and a 10% reserve requirement would need to keep $50 million in reserves. The Federal Reserve used a tiered system before March 2020 that based requirements on deposit size:

All but one of these deposits came under the “reserve requirement exemption amount” (0% ratio)

Medium deposits needed a 3% requirement

Large deposits faced a 10% requirement

The calculation schedule depends on how often banks report to regulators. Banks document their transaction accounts and other deposits on the “FR 2900” form weekly or quarterly. These reserve requirements work on a “lagged” basis – reserves calculated now must be kept during a future 14-day maintenance period.

Vault cash vs. reserves at the central bank

Banks can meet required reserves in two main ways: they can keep physical cash in their vaults or electronic balances at a Federal Reserve Bank. Most banks use both methods together.

“Vault cash” means the actual currency banks keep on hand to handle daily transactions like customer withdrawals. This cash helps meet reserve requirements and covers immediate operational needs. Smart banks keep enough cash reserves to handle expected customer demands, like holiday withdrawals, even without official requirements.

Banks don’t need to keep any reserve balance if their vault cash exceeds requirements. But if it doesn’t, they must keep extra reserves in their Federal Reserve account. The math is simple:

Reserve Balance Requirement = Total Reserve Requirement – Average Vault Cash

Some smaller banks have a “pass-through relationship” where they keep reserves at bigger banks that hold Federal Reserve balances for them. Community banks find this makes reserve management easier while staying compliant.

What happens if a bank falls short

Banks have several options to fix the problem when their reserves drop too low. They just need to borrow funds quickly from other sources.

Banks with low reserves can borrow from other financial institutions through the interbank lending market. Banks that have extra reserves lend to those that need them and charge interest based on the federal funds rate. Banks can also borrow straight from the Federal Reserve’s “discount window,” which might be easier but carries some stigma.

Running short of reserves used to have serious consequences. The National Banking Act stopped banks from making new loans or paying dividends until they restored their reserves. Banks that stayed deficient beyond 30 days risked having the Comptroller appoint someone to take over.

Modern enforcement still matters a lot. Banks must quickly fix reserve shortfalls or face regulatory action. These procedures will apply again if reserve requirements come back, even though they’re currently at zero.

Past banking crises showed why these practical details matter. Interbank deposits counted toward reserve requirements during the National Banking Era but didn’t work well during panics. This taught central banks to provide liquidity in other ways instead of only using reserve requirements to keep the financial system stable.

The Federal Reserve Requirement System Explained

The Federal Reserve’s Regulation D has shaped how banks manage their reserves for decades. This regulatory framework, created under Section 19 of the Federal Reserve Act, went through its most important change in March 2020.

Reserve tiers under Regulation D before 2020

The Federal Reserve used a multi-tiered system before March 2020. This system applied different reserve ratios based on a bank’s transaction account size. The system had three distinct tiers:

A “reserve requirement exemption amount” where smaller deposit amounts faced 0% reserve requirements

A “low reserve tranche” where deposits above the exemption amount but below a certain threshold required a 3% reserve ratio

Deposits exceeding the low reserve tranche that required a 10% reserve ratio

The exemption amount and low reserve tranche weren’t fixed values. The Federal Reserve Act specified a formula to adjust them yearly. These adjustments continued to appear in the Federal Register even after the Fed eliminated reserve requirements.

Why the Fed reduced reserve requirements to 0%

The Federal Reserve made a historic decision as COVID-19 created economic uncertainty in March 2020. On March 15, 2020, the Board announced that reserve requirement ratios would drop to zero percent starting March 26, 2020.

This major move wasn’t just about the pandemic. The Federal Reserve had started moving to an “ample reserves” regime in January 2019. Reserve requirements no longer played a crucial role in monetary policy implementation under this new framework.

Banks and businesses benefited from eliminating reserve requirements in two ways. It freed up liquidity for thousands of depository institutions to support lending. The change also matched the Fed’s new approach to monetary policy, which relies on interest rates rather than controlling reserves.

Effect of the 2020 policy move on U.S. banks

U.S. banks saw several notable changes with the zero-percent reserve requirement. The change removed a regulatory burden that had limited banks’ lending capacity.

Studies show this policy helped banks lend more during the pandemic crisis. Banks could now use funds previously locked as required reserves to extend more credit when businesses needed it most.

This transformation changed how banks handle their liquidity. There’s no difference between required and excess reserves now, so all reserve balances count toward regulatory liquidity requirements. Banks no longer need complicated “sweep” programs they once used to minimize required reserves.

The Federal Reserve still calculates and publishes the reserve requirement exemption amount and low reserve tranche yearly, as law requires. These annual adjustments continue despite the zero-percent requirement.

How Reserve Requirements Affect You and the Economy

Reserve requirements directly affect your daily financial life – from the interest you earn on savings to how easily you can get a loan. The ripple effects spread throughout the economy whenever central banks adjust these requirements.

How reserve rules influence loan availability

Reserve requirements determine how much money banks can lend. Banks gained immediate access to previously restricted funds after the Fed reduced requirements to zero percent in March 2020. This change lets financial institutions extend more credit to businesses and people who need loans.

Banks can use more of their deposits to lend money when reserve requirements are lower. People find it easier to get personal loans, mortgages, and business financing as a result.

The zero-reserve policy during the pandemic clearly demonstrates this principle. This big change freed up liquidity for thousands of banks to support lending to households and businesses during uncertain economic times.

The expanded lending comes with potential risks. Research shows lower requirements boost economic activity but may encourage banks to take more risks. Some banks might start financing riskier assets with higher returns to compensate for costs.

Connection between reserve levels and interest rates

Reserve requirements shape interest rates throughout the economy. Interest rates usually decrease when central banks lower reserve requirements. Banks with more money to lend often compete by offering better rates.

When requirements become stricter, the opposite happens. Banks must keep more cash in reserve, which leaves less money for loans. As a result, consumers face higher borrowing costs and stricter lending standards.

Many consumer interest rates depend on the federal funds rate – the rate banks charge each other for overnight loans. Changes in reserve requirements affect this key rate and extend to:

Mortgage rates

Credit card interest

Auto loan pricing

Business financing costs

These changes create important economic tradeoffs. Research shows that stricter reserve requirements reduce credit cycle swings and make financial crises less frequent and severe. The stability this provides outweighs the initial slowdown in economic growth.

Reserve requirements balance two competing priorities: making credit accessible while keeping the financial system stable.

Materials and Methods: How Reserve Ratios Are Set and Adjusted

The Federal Reserve follows a careful, methodical process backed by law to set reserve requirement percentages. They don’t pick random numbers. Specific legal guidelines and adjustment formulas guide their decisions.

Role of the Federal Reserve Board in setting ratios

The Federal Reserve System’s Board of Governors has exclusive authority to set reserve requirements for depository institutions. Section 19 of the Federal Reserve Act grants this power and states these requirements exist “solely to implement monetary policy”.

The law gives the Fed flexibility to adjust these requirements. They can even reduce them to zero if needed. This power proved vital in March 2020 when the Board dropped requirements to zero percent.

The Board’s actions must line up with its legal mandate. Regulation D states that reserve requirements serve one purpose: “facilitating the implementation of monetary policy”.

The Federal Reserve can’t change these requirements randomly to generate revenue or punish banks.

Annual indexation of exemption and low reserve tranche

The Federal Reserve Board announces adjustments to two vital parts of the reserve requirement system each year:

The reserve requirement exemption amount – deposits that don’t need any reserve requirement

The low reserve tranche – deposits that qualify for a lower reserve ratio

The Federal Reserve Act specifies formulas for these adjustments. The exemption amount adjustment equals 80% of the percentage increase in total reservable liabilities at all depository institutions. This measurement happens yearly on June 30.

The low reserve tranche adjustment works the same way. It equals 80% of the increase or decrease in total transaction accounts, measured yearly.

The Federal Reserve kept the exemption amount at $36.10 million for 2024, unchanged from 2023. The low reserve tranche dropped to $644.00 million from $691.70 million in 2023. These numbers will change to $37.80 million and $645.80 million in 2025.

The law requires these annual calculations even with zero percent reserve requirements currently in place. Banks might not need to hold reserves now, but the adjustments continue.

Conclusion

The Federal Reserve’s historic decision to set reserve requirements at zero percent in 2020 marked the most important transformation since their 1863 introduction. This radical alteration redefined how banks manage their deposits and lending practices.

Banks still maintain voluntary reserves to meet operational needs and regulatory requirements. The relevance of reserve requirements in shaping monetary policy continues despite no longer restricting bank lending.

Modern banking practices have changed dramatically. Central banks now prefer using interest rates and other tools for monetary policy management instead of traditional reserve ratios.

Reserve requirements provide crucial insights into bank operations and their decision-making process for lending and interest rates. These banking choices affect our daily financial activities, from mortgage approvals to savings account returns.

The Federal Reserve’s annual calculation of reserve requirement adjustments points to this tool’s potential role in future policy decisions. This approach will give a banking system the adaptability it needs under varying economic conditions.